The Long Thread of Realism: How Today’s Painters Are Still Speaking an Old Language

- Hope Blakely

- Jan 5

- 4 min read

There’s a moment that sneaks up on you as a painter.

It doesn’t happen while you’re learning clouds or wrestling with a mountain knife. It doesn’t show up when you’re copying a reference or following along with a lesson. It arrives later — quietly — when you realize that what you’re doing feels older than the lesson that taught it to you.

That was the moment I began to look backward.

Because realism — real, representational painting — didn’t begin with Bob Ross. It didn’t begin with Bill Alexander either. And yet, somehow, when I stand in front of a canvas today, I feel echoes of something much older guiding my hand.

Not rules.Not formulas.But intention.

Looking Back Before We Look Forward

Long before television shows and workshops and online tutorials, painters were standing outdoors with heavy boxes of paint, trying to answer the same question artists still ask today:

How do I capture what this place feels like?

They studied light not because it was fashionable, but because light tells the truth. They layered paint slowly, deliberately, because depth mattered. Mountains were painted to feel immovable. Forests were painted with reverence. Skies weren’t backgrounds — they were emotional architecture.

Those painters weren’t thinking in movements or labels. They were simply trying to honor what they saw.

And that mindset never disappeared.

The Middle Years: When Realism Refused to Die

As abstraction and modern art took center stage, realism didn’t vanish — it just grew quieter.

Some artists kept painting landscapes, seascapes, and people not because it sold well, but because it made sense to them. Others began teaching, passing along techniques person to person instead of through institutions. Painting became something you did, not something you had to justify.

This is where the bridge begins to form.

The idea that realism could be learned.That beauty wasn’t elitist.That skill and joy could exist together.

Sound familiar?

A Quiet Pause (Just for a Moment)

At one point, I started lining things up — not as timelines or movements, but as shared priorities. When you do that, the continuity becomes surprisingly clear.

A Simple Way to See the Continuity

What Matters Most | Then | The Middle | Now |

Purpose | Honor nature | Make realism reachable | Express mood & meaning |

How Paint Is Used | Layered, deliberate | Direct, confident | Refined but personal |

Light | Observed & dramatic | Simplified & joyful | Controlled & emotional |

Teaching | Master to apprentice | “Anyone can paint” | Skill + individuality |

The Feeling Left Behind | Awe | Calm | Atmosphere |

That’s all the chart needs to say.

Because once you see it, you don’t need to stare at it for long.

Some of the Voices in This Long Conversation

No single painter owns this lineage. It’s a conversation carried quietly across generations — sometimes loudly, sometimes almost unnoticed — but always recognizable if you know how to listen.

Earlier voices, who shaped how painters learned to see light, land, and atmosphere, include artists like Albert Bierstadt, Frederic Edwin Church, Asher B. Durand, and Ivan Shishkin — painters whose work carried reverence, scale, and emotional weight long before realism had a name attached to it.

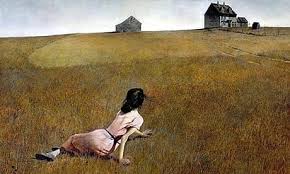

Later came bridge figures — artists like John Singer Sargent, Winslow Homer, and Andrew Wyeth — who kept representational painting alive during a time when much of the art world was moving away from it.

And then there are the teachers, who believed realism didn’t belong behind museum glass, but in studios, classrooms, and living rooms: Bill Alexander, Bob Ross, and those who carried that spirit forward in their own way — painters and educators like Gary Jenkins, Kevin Hill, and Dana Jester.

Not as a hierarchy.Not as a straight line.But as a shared way of seeing.

Back to the Fire

Seeing that connection didn’t make painting feel smaller to me.

It made it feel deeper.

Because what’s being passed down isn’t a technique. It’s a way of seeing. Bill Alexander brought intensity and confidence. Bob Ross brought warmth and accessibility. Modern painters bring reflection, atmosphere, and personal voice.

We’re not breaking from tradition.We’re continuing it.

The tools change. The pace changes. The language softens or sharpens depending on the era. But the heart of realism — the desire to make something recognizable, grounded, and emotionally true — remains intact.

Where That Leaves Us Today

When people ask whether modern realism is “real art,” I don’t answer with arguments anymore.

I answer by painting.

Because the same values that guided painters centuries ago — light, structure, mood, honesty — are still guiding hands today. They guided mine when I first learned. They guide me now as I move beyond imitation and into my own voice.

Realism isn’t behind us.

It’s a long conversation — and we’re still speaking it.

Thanks for reading,Hope Blakely

Keeping Happy Trees Alive 🌲

If this piece resonated with you, I’d love to hear your thoughts. Feel free to leave a comment below, and don’t forget to tap the little heart to let me know you enjoyed it. Your support helps keep these conversations — and this long thread of realism — going.

Comments